Enough carrots for Putin. For better negotiations, serve ‘maximum pressure’ instead.

The United States, Ukraine, the European Union, and the Russian Federation have been riding a diplomatic rollercoaster for the past month, with the announced March 18 call between US President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin the next turn ahead. Amid the furious pace, chances for a sustainable peace in Ukraine remain very much in question. In particular, the past few weeks have witnessed a flurry of shuttle diplomacy by the Trump administration, with Secretary of State Marco Rubio and National Security Advisor Mike Waltz securing an agreement for an immediate thirty-day cease-fire from top Ukrainian government officials in meetings held in Riyadh. The next step is up to the Kremlin. And so far, Putin seems content to allow progress to slow to a glacial pace.

Putin has effectively—though not yet formally—rejected the US and Ukrainian offer of an immediate thirty-day cease-fire. He is raising conditions untenable for the Ukrainian side and inimical to a sustained settlement while he attempts to claim to be an adherent of “peace.” Far from preparing to halt his unprovoked aggression toward his democratic neighbor, Putin has returned to calls to address the “root causes of the crisis,” by which he appears to mean Ukraine’s independence from Moscow. At the same time, he is publicly lobbying the United States and Europe to abandon Ukraine.

Trump may yet convince Putin to agree to an immediate, unconditional cease-fire. If he does not, the United States should increase pressure to force Putin to the negotiating table and accept terms essential to a sustainable peace, including Ukraine’s long-term security. To start with, the administration should turn up the pressure on the Kremlin via comprehensive sanctions and technology export controls that target Russia’s main economic lifeline: energy exports.

The United States ought to be seeking to replace Russia on world energy markets, not allowing Russia to come back.

The Trump administration should deploy a “maximum pressure” approach, especially on energy, since Russia’s oil and gas revenues continue to play an outsized role in Moscow’s ability to fund its military aggression in Ukraine. Given the domestic cashflow challenges already plaguing Moscow, a broader swath of energy sanctions and controls on oil field service technologies, if aggressively and comprehensively enforced, could help create the level of pressure required. And the administration has options.

The Trump White House has a wide menu available to continue to mount energy sanctions and restrictions on Putin’s Kremlin, and it appears to have taken the first step toward such a strategy in the past few days. On March 12, the US Department of the Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) allowed the expiration of a temporary general license that had been provided by the Biden administration for firms to continue to process transactions related to energy purchases with a set of Russian financial institutions. This loophole has been open in various forms since just after Russia’s full-scale invasion began in February 2022, and it is finally (and mercifully) now closed, restricting a key conduit for Russia to financially benefit from its energy exports.

First and foremost, the Kremlin-backed Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipelines must be a priority for the White House. Headlines related to their possible revival continue to appear, but the Trump administration should work to prevent their reestablishment. One way to do this would be for the White House to issue an executive order levying permanent blocking sanctions against Russian energy export pipelines, such as the pair of Nord Stream and TurkStream projects. These sanctions could also apply to the Yamal-Europe pipeline and other similar Kremlin-backed schemes, as well as Russian liquefied natural gas export terminals and vessels. The United States ought to be seeking to replace Russia on world energy markets, not allowing Russia to come back.

The administration, led by OFAC and the US intelligence community, should also intensify efforts to track, identify, and designate all vessels that are shown to be a part of Russia’s so-called “shadow fleet” of underinsured, sanctions-and-price-cap-busting oil tankers. The push to sanction Putin’s shadow fleet has been underway for some time, but due to the scale of the fleet, enforcement has consistently been behind the curve.

The United States (as well as the European Union and United Kingdom) should impose sanctions on all additional vessels from the shadow fleet that it can identify—and deploy secondary sanctions against ports that receive them. For Russia to replace its sanctioned tankers with new “shadow fleet” tankers through secondary-market purchases would likely take time and resources. Moscow is unlikely to put that much capital at risk, especially if it believes the United States might quickly add those tankers to the OFAC target list as well.

But it’s not enough to go after just the shadow fleet. Should shadow-fleet-tanker listings force Russia to become more reliant on mainstream tankers, Moscow may attempt to defraud those vessels into carrying cargoes priced above the sixty-dollars-per-barrel price cap by continuing to provide fraudulent price attestations. Under the price cap, mainstream tanker owners in the Russia trade are required to receive a price attestation from a trader handling the trade, but not the underlying contracts, which many trading counterparties would refuse to divulge.

To reduce the risk of attestation fraud, OFAC could develop a “white list” of well-established oil traders with high levels of exposure to and legal accountability in the United States. OFAC would then require that mainstream tankers only lift Russian oil if a white-listed trader is handling the sale and providing the price attestation. This would put additional pressure on Russia to sell its oil through white-listed traders when using mainstream vessels.

As another maximum pressure option, the United States could borrow an idea from the sanctions regime on Iran. One of its most aggressive features was the demand, originally in legislation, that Iran’s oil customers reduce their purchases every six months, backed up by the threat of severe financial sanctions, including against the purchasing country’s central banks. The United States could introduce a similar regime against Russian oil sales, keeping in mind the need not to risk a spike in global oil prices by forcing too much Russian oil off the market and, hopefully, in coordination with other oil producers, such as Saudi Arabia.

These energy sanctions could be coupled with additional financial sanctions. The United States and Europe acted gradually to impose financial sanctions on Russia’s big state banks and some private banks, along with sectoral sanctions on technology and some Russian companies. This creates a complex sanctions regime in which some trade and finance is banned but much remains allowed, with gray areas and loopholes. The United States, acting with Europe, should consider a general financial embargo and even a trade embargo on Russia, with specified categories of permitted trade and related finance, such as medicine, limited energy, food, and other transactions. In addition, sanctions on high-tech energy and other technologies—especially those that could be repurposed to support Russian military supply chains—should be deepened to the greatest extent possible, backed up with the threat of secondary sanctions.

To help with all this, the Trump administration should significantly scale up executive branch staffing on sanctions monitoring, targeting, and enforcement through a reallocation of existing personnel or external hires. Additionally, the administration should foster public-private partnerships with commercial satellite imaging companies to allow the United States’ academic and expert communities to build on US government capacity to track and identify Russia’s shadow fleet. Moreover, these vessels should be designated under existing sanctions authorities.

The White House need not act alone here—statutorily mandated sanctions always send a stronger message than executive orders. Therefore, the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee and Banking Committee can play a big role in showing an all-of-government pressure campaign is in the offing against the Kremlin. Senator Lindsey Graham’s proposed “bone-breaking” Russia sanctions package is one of many strong signals that demonstrate that Congress is willing to strengthen the US push for a sustainable peace in Ukraine. Furthermore, the White House should capitalize on some European leaders’ warming attitude toward increasing Russia sanctions as well as seizing and using frozen Russian central bank assets to support Ukraine’s ability, even after a cease-fire, to rebuild and rearm in the face of what is likely to be sustained Russian pressure regardless of an agreement to halt fighting in Ukraine.

In other words, by wielding the sanctions sticks the White House, Congress, and European allies already hold, the Trump administration can bolster Ukrainian military resolve and its own policy of seeking an end to the war on favorable terms.

Otherwise, Putin will simply push to have his carrot cake and eat it too.

Benjamin L. Schmitt, PhD, is a senior fellow at the Department of Physics and Astronomy, the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy and Perry World House at the University of Pennsylvania, a senior fellow for democratic resilience at the Center for European Policy Analysis, and an associate of the Harvard-Ukrainian Research Institute. Schmitt is also a co-founder of the Duke University Space Diplomacy Lab, and a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations. Follow him on X @BLSchmitt.

Richard L. Morningstar is the founding chairman of the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center. He has previously served as US ambassador to the European Union, US ambassador to the Republic of Azerbaijan, and as US special envoy for Eurasian energy affairs.

Daniel Fried is the Weiser Family distinguished fellow at the Atlantic Council. He is also on the board of directors of the National Endowment for Democracy and a visiting professor at Warsaw University. Fried served for forty years in the US Foreign Service. He is a former US ambassador to Poland, assistant secretary of state for Europe, and coordinator of sanctions policy. Follow him on X @AmbDanFried.

Further reading

Fri, Mar 14, 2025

What game is Putin playing in the cease-fire talks?

Fast Thinking By

Our experts parse the Kremlin’s official reaction to the United States’ proposal for a cease-fire in Ukraine.

Fri, Mar 7, 2025

Former US Senator Rob Portman: How to achieve a successful cease-fire and lasting peace in Ukraine

New Atlanticist By

“We should all want the war on Ukraine to end, and we should welcome negotiations. But we should negotiate from a position of strength,” writes a former US senator.

Mon, Mar 10, 2025

Here’s a Ukraine peace plan Trump can use to deter—not appease—Putin

Inflection Points By Frederick Kempe

Putting the possibility of NATO membership for Ukraine squarely on the table provides leverage in negotiations with Russia, a new essay argues.

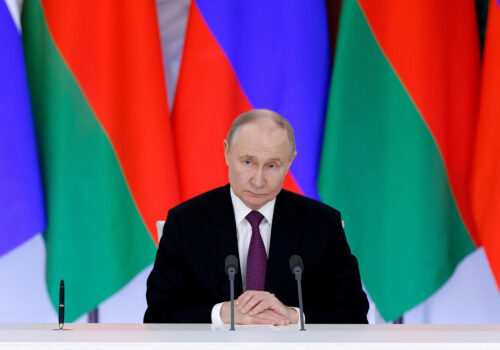

Image: Russian President Vladimir Putin chairs a meeting with members of the Security Council via video link at the Novo-Ogaryovo state residence outside Moscow, Russia March 14, 2025. Sputnik/Mikhail Metzel/Pool via REUTERS